Fundamental Vibrations and Overtones in Spectrometry

Fundamental vibrations and overtones are central physical concepts that make NIR spectrometry possible in the first place. Enough reason to take a closer look at the underlying principles.

Everything vibrates

The fact that atoms constantly vibrate is often vaguely remembered from school lessons. But it’s not just individual atoms that vibrate - molecules are not static structures either.

When atoms bond to form molecules, these bonds are not rigid but flexible, like being connected by rubber bands or springs.

In physics, various models of differing complexity have been developed to describe the causes and effects of these vibrations. The most important models are the classical harmonic oscillator, the quantum mechanical oscillator, and the anharmonic oscillator. The latter explains most aspects of real molecules but is also mathematically more complex. Fortunately, they all build on each other. So if we examine them one by one, they become quite understandable.

The Classical Harmonic Oscillator

The harmonic oscillator is a simple model - incorrect, but useful for basic understanding. It uses a mechanical picture of molecules: the atoms of a molecule are visualized as spheres connected by springs.

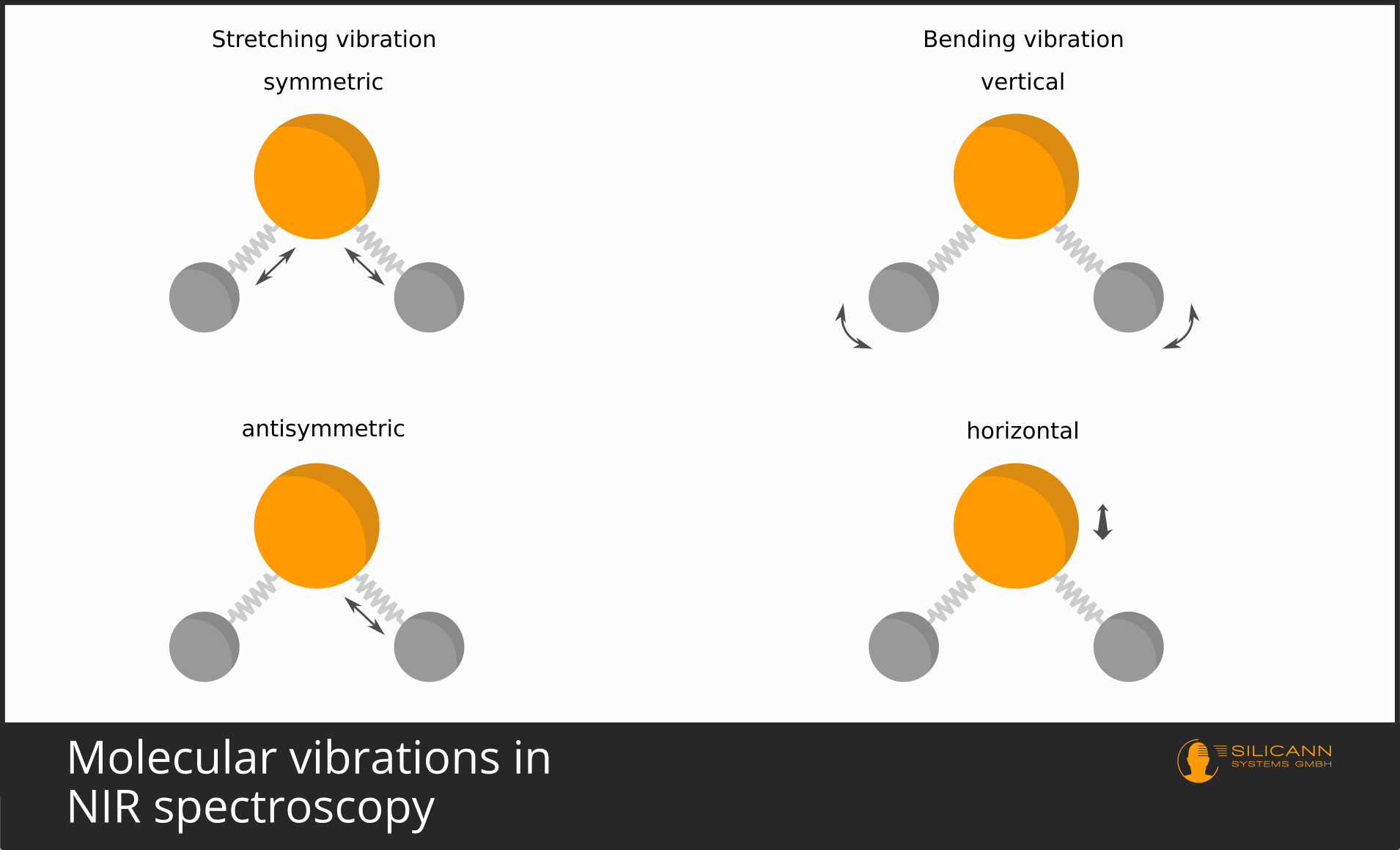

These springs allow the connected atoms a certain flexibility. The spring can be stretched and compressed. This is known as a stretching vibration. Bending of the spring is also possible - in this case, the bond angle between atoms changes. Such a vibration is called a bending or deformation vibration.

Springs are familiar territory in mechanics. In our molecular model, the spring constant from mechanics is simply referred to as the force constant \(k\). The spring constant describes the stiffness or rigidity of the spring. In chemistry, this corresponds to the strength of the bond between atoms. A triple bond is stronger than a single bond - the force constant \(k\) is higher in a triple bond.

Now, if we had a mass, we could simply use the idea of a mechanical spring pendulum, in which the oscillation frequency arises from the spring constant and mass.

In the spring pendulum, one end of the spring is fixed to a wall, and a mass hangs from the other end. We don't have this luxury with molecules, but we can use a trick.

Let’s consider a simple molecule with just two atoms: HCl. Connected by a spring, these two atoms, H and Cl, vibrate back and forth. However, the atoms are not actually fixed to any wall - they are, when viewed from a large enough distance, essentially floating freely in space. The atoms thus vibrate relative to each other, each moving slightly toward and away from the other. The hydrogen atom is much lighter than the chlorine atom and therefore moves more relative to the chlorine atom. But the chlorine atom still vibrates significantly enough that it cannot be modeled as a fixed wall. For modeling purposes, however, this would be very convenient - because a mass moving relative to a fixed wall is far easier to handle. To solve this, the concept of the reduced mass \(µ\) was introduced. The masses of both atoms are combined as follows:

\(μ = \frac {m_1 \cdot m_2}{(m_1+m_2)}\)

In mechanics, the oscillation frequency is calculated as:

\(\omega_0 = \sqrt{\frac {D\: ( =\: spring \: constant)}{m\: ( =\: mass)}}\)

We can now apply this same formula to the molecule. The connecting spring becomes the molecular bond, the spring constant \(D\) becomes the force constant \(K\), and the mass \(m\) becomes the reduced mass \(µ\). We must only remember that \(\omega\) describes angular frequency, while we need the frequency \(v\). Therefore, we divide by \({2\pi}\):

\(v_{vib} = \frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac {k}{µ}}\)

If we divide the speed of light by this frequency, we obtain a wavelength - the wavelength at which this excited molecule would vibrate.

\(λ = \frac {c}{v}\)

In other words: if we know the atoms of the molecule and the bond strength, can’t we then predict the position where this molecular vibration would appear in the spectrum?

The Quantum Mechanical Harmonic Oscillator - Leaving Classical Mechanics

Almost. Unfortunately, it’s not quite as simple as in this purely mechanical model. What this model gets right: the lighter the atoms and the stronger the bond, the higher the frequency and the shorter the wavelength.

A major difference from reality: molecules cannot be excited to vibrate with arbitrary amounts of energy. Instead, molecules can only occupy specific vibrational energy levels, and can only transition from their current level to the next higher or lower level. Jumps across two or more levels are not allowed.

The required energy (the vibrational quantum or energy difference ΔE) we have almost already calculated - it is \(hv_{vib}\). \(v_{vib}\) is the frequency derived above, now multiplied by Planck’s constant \(h\).

Because this energy still depends on \(v_{vib}\), it remains dependent on the exact structure of the molecule.

If we want to know not just the energy differen, but the total energy required for a specific energy level, we can calculate it as follows:

\(E = hv_{vib} ( v + \frac{1}{2} )\)

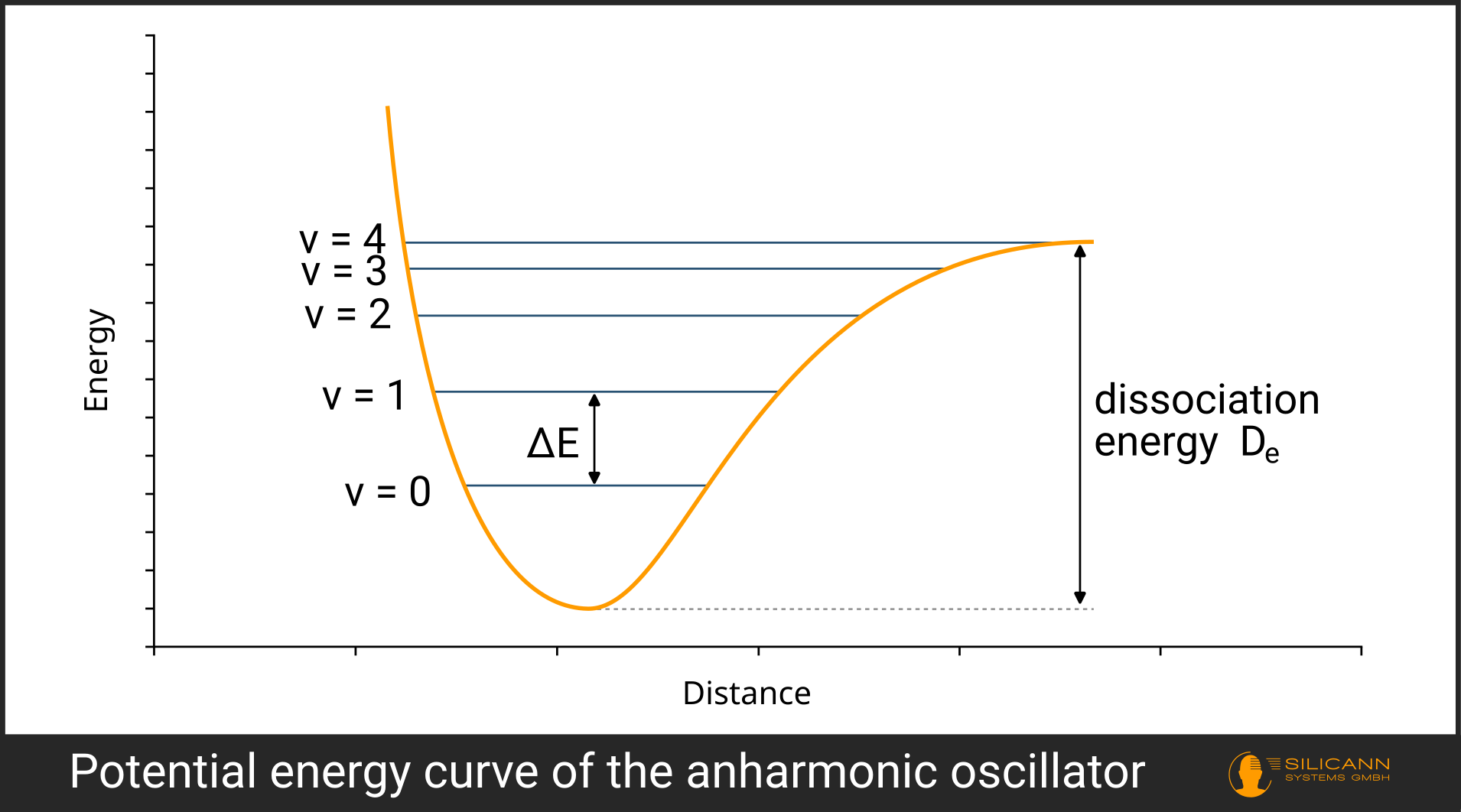

The \(v\) in the parentheses denotes the so-called vibrational quantum number and simply indicates the level to which the system is excited (see illustration).

Thus, the harmonic oscillator already describes the functioning of vibrations at different levels. Due to so-called selection rules, jumps to the next-next level (e.g., \(v = 0 \rightarrow v = 2\)) are not permitted, but multiple excitations of the same vibration (e.g., through collisions with other molecules) are still possible.

Since we can already determine the wavelengths at which we would observe these vibrations in the spectrum, this model can be tested empirically. Anyone performing this experiment will notice that the multiples of the fundamental vibration are not quite at the "correct" position: with each higher vibrational level, the peak in the spectrum shifts further toward longer wavelengths. In other words, each additional overtone requires slightly less energy than predicted by the harmonic model, rather than exactly the same amount.

The Anharmonic Oscillator

The reason becomes plausible if we imagine the molecule mechanically. Consider a simple O₂ molecule. We hold one oxygen atom fixed while the other vibrates wildly back and forth. We now add one vibrational quantum at a time, and each time the free oxygen atom vibrates more intensely. Eventually, a limit is reached: the vibration becomes so strong that the free oxygen atom breaks away, and the two atoms exist only separately, no longer as a molecule.

A similar situation is modeled in the anharmonic oscillator. It extends the harmonic oscillator so that we cannot add vibrational quanta infinitely to raise the molecule to arbitrarily high vibrational levels. Instead, each higher level requires less energy, until the molecule reaches a point where it dissociates - i.e. breaks apart. The energy required for this is called the dissociation energy \(D_e\).

Mathematically, the formula from above is extended to include anharmonicity, with the dissociation energy \(D_e\) playing a key role.

\(E = hv_{vib} (v + \frac{1}{2}) − h^2v^2_{vib} (v+1)^2 \frac{1}{4D_e}\)

\(D_e\) is the only new variable. Those interested in deriving the anharmonicity constant from the dissociation energy can explore the concepts of the Morse potential and the Schrödinger equation.

In the visualization, it can be seen that the right-hand side of the potential no longer rises infinitely but levels off at the dissociation energy.

Fundamental and Overtone Vibrations via Absorption

Anharmonicity has further consequences. Most notably, in the harmonic model, transitions across multiple vibrational levels (\(v = 0 \rightarrow v = 2\), etc.) were not allowed, but they are now permitted—although they occur much less frequently, only about 1–10% as often per skipped level compared to the fundamental vibration.

How is the molecule excited to vibrate? By electromagnetic radiation. The photons in the radiation must provide exactly the amount of energy corresponding to the energy difference ΔE. Photon energy is proportional to wavenumber, and thus the required wavelength can be easily calculated (see Converting Wavenumber to Wavelength).

When a photon of exactly this wavelength hits the molecule, the molecule is excited from vibrational level 0 to level 1 (\(v = 0 \rightarrow v = 1\)). This is the molecule's fundamental vibration.

At the moment of excitation, absorption occurs: the photon's energy is absorbed by the molecule and converted into a more pronounced vibration. This is the basic principle of infrared spectrometry: a radiation source (usually a thermal lamp or IR LED) emits a broad spectrum of infrared wavelengths, and after interacting with the molecule, the absorbed wavelength will be missing or reduced in the spectrum. Because the exact required wavelength results from the molecule’s specific structure, this allows us to infer the type of molecule that was hit. Unknown substances and mixtures can thus be identified by irradiating them with infrared light and analyzing the result with a spectrometer.

It may also happen - though much less likely - that the molecule absorbs enough energy to skip one or even two energy levels and jump directly to a higher level. These are then the first overtone (\(v = 0 \rightarrow v = 2\)), the second overtone (\(v = 0 \rightarrow v = 3\)), etc.

MIR vs. NIR

Most fundamental vibrations occur in the mid-infrared range (MIR) at room temperature. Yet near-infrared (NIR) spectrometry is far more common, despite working only with much weaker overtones. There are several reasons.

First, the high absorption in the MIR range is its own biggest obstacle: the excitation radiation can penetrate solid materials only very poorly. To avoid this, samples must often be prepared, for example, as pressed pellets. This is time-consuming and expensive, restricting MIR spectrometry largely to laboratory applications requiring the highest precision.

Additionally, water absorbs very strongly in this region, meaning the signal of interest in moist samples can easily be masked by vibrations from water molecules.

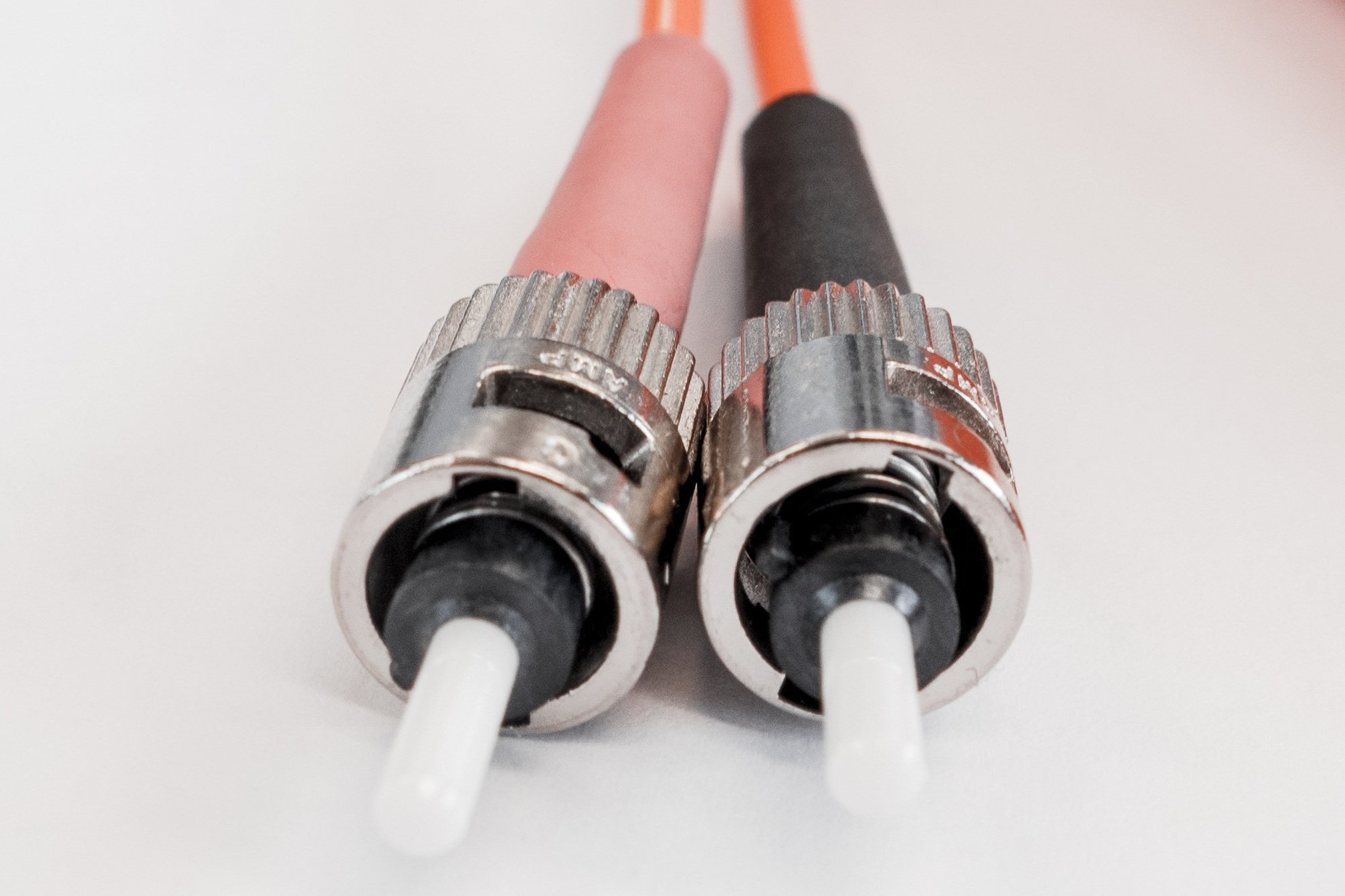

Finally, many established components in spectroscopy are not transparent in the MIR range. For example, standard optical fibers absorb MIR radiation, ruling them out for MIR spectroscopy. The same applies to various materials used for lenses and other optical components. Alternatives exist, but they are significantly more expensive.

NIR spectrometry is therefore optically and mechanically much easier to implement. Because it requires no sample preparation, it can also be used continuously for process monitoring (e.g., over a conveyor belt).

The Dipole Moment – Why NIR Spectrometry Works at All

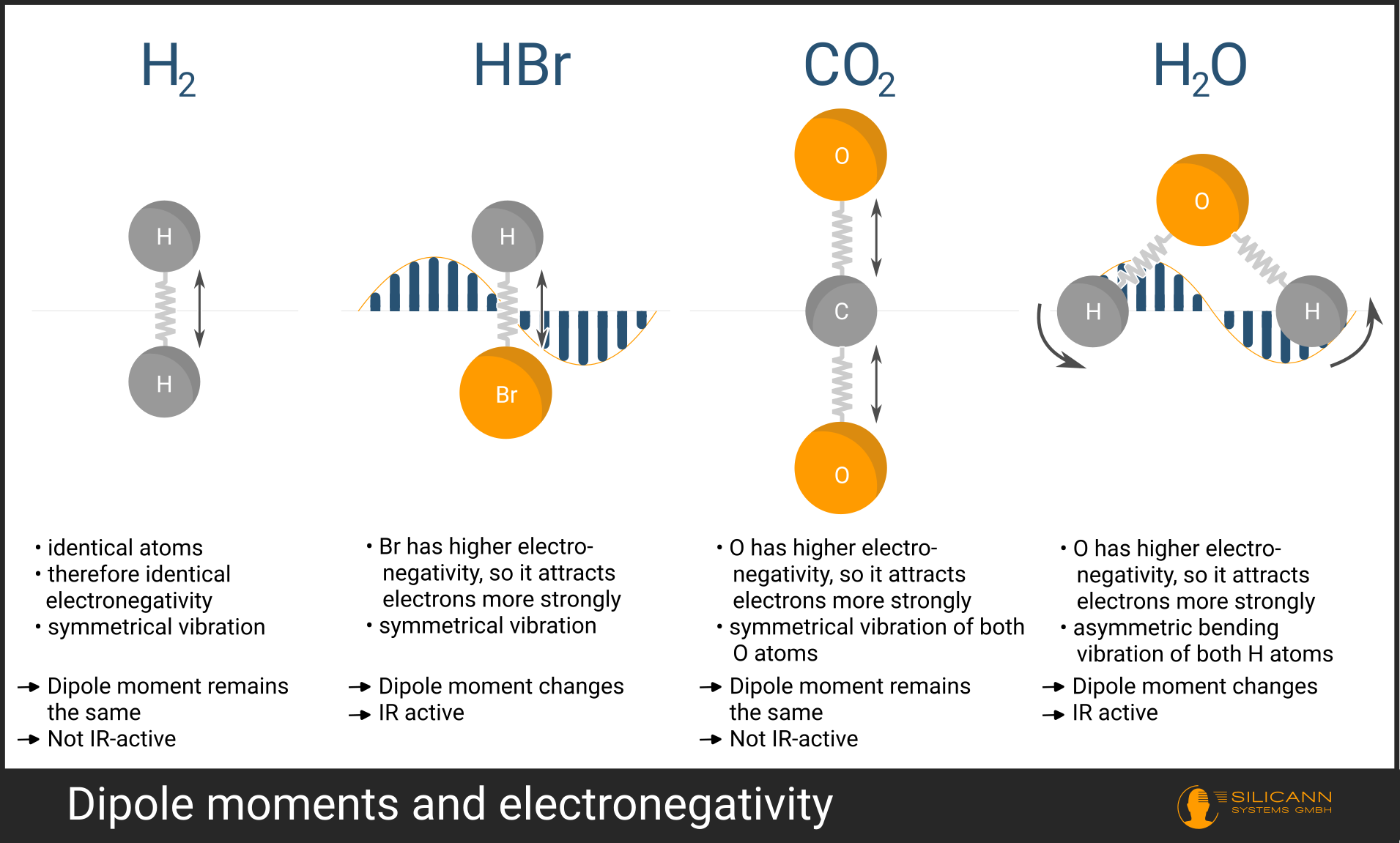

Can every molecule be analyzed using absorption spectrometry? Unfortunately, no - many molecules are not visible in the infrared, even though their structure suggests a vibrational frequency should exist there. Such molecules are called IR-inactive. Whether a molecule is IR-active depends on its exact shape.

The molecule’s shape determines whether and how strongly electrical charge is spatially separated within it. This is known as the dipole moment. As a mnemonic, think of the poles of a bar magnet.

A dipole moment arises mainly for two reasons:

- The atoms in the molecule attract electrons with different strengths. The key term here is electronegativity. The bonding of atoms into a molecule occurs by sharing one or more electrons. However, atoms may differ in size and charge, causing electrons to be closer to one atom than the other. In this case, we speak of partially positively charged (\(δ+\)) and partially negatively charged (\(δ-\)) atoms.

- The geometry of the molecule. For example, the \(CO_2\) molecule is linear, with atoms lying along one axis. If the oxygen atoms simultaneously undergo a stretching vibration, the total charge distribution remains unchanged—both oxygen atoms move in exactly opposite directions, and their partial charges cancel each other out. This molecular vibration is therefore IR-inactive

For a molecule to absorb infrared radiation, its dipole moment must change during vibration. This is strongly true, for example, for the \(H_2O\) molecule. The hydrogen atoms are bent, and stretch asymmetrically. In this way, the dipole moment changes significantly during the vibration.

Why is the dipole moment a prerequisite for visibility in NIR spectrometry? The infrared radiation used to irradiate a molecule is an oscillating electric field. Mechanically speaking: the molecule acts like an antenna—but only if it has a dipole moment. The field of the radiation itself oscillates back and forth. When the field points "up," the negative side of the molecule is pulled "up" and the positive side "down." Then the field reverses direction, and so on. If this occurs at the same frequency as the molecule's vibration, resonance occurs. At the moment of resonance, the molecule is elevated to a higher vibrational level.

Degrees of Freedom – One Molecule Can Vibrate in Multiple Ways

At the beginning, it was briefly mentioned that molecules can vibrate in different ways. Vibrations are grouped into stretching and bending vibrations.

Stretching vibrations describe the elongation and compression of a molecular bond. In molecules like water (\(H_2O\)), the hydrogen atoms can either move inward and outward simultaneously (symmetric stretching vibration), or one moves inward while the other moves outward at the same time (asymmetric stretching vibration).

For bending vibrations, there is even more variety. In general, the bond angle between atoms changes. Possible types include scissoring, rocking, wagging, and twisting. Bending vibrations are generally found in the longer-wavelength IR region.

The key point here is that a single molecule, depending on its exact structure, can have several possible vibrational modes. These possibilities are known as the degrees of freedom of the molecule.

A single atom in three-dimensional space can vibrate in exactly these three dimensions. It thus has 3 degrees of freedom. A molecule made up of \(N\) atoms has potentially \(3N\) degrees of freedom. However, not all of these are relevant depending on the specific structure.

For example, the \(CO_2\) molecule is linear. Rotation along its long axis is irrelevant because the moment of inertia is zero, and thus the energy required for excitation would be infinite. In this way, different molecular geometries eliminate different numbers of degrees of freedom.

Each additional degree of freedom - provided a dipole moment exists - offers another opportunity for infrared absorption. Thus, a single molecule can appear at multiple positions in the spectrum.

This fact can even be exploited to determine the chemical structure of an unknown substance. For example, a \(C-H\) vibration always occurs at the same wavenumber, regardless of the molecule it appears in. With enough such clues, the exact molecular structure can be deciphered.

However, this is reserved for highly precise laboratory measurements and is, for example, a suitable application for MIR spectrometry. In practice, NIR spectrometry is mostly concerned with detecting the presence or determining the mixture ratio of known substances. Because this can be achieved simply by shining light onto a sample (combined with mathematically more complex data processing), NIR spectrometers are frequently found in quality control, for instance in the food industry.